Europes's Inevitable Loss of its Sole Titanium Sponge Producer

Zaporizhzhia Titanium-Magnesium Plant (ZTMP): Ukraine's Titanium Treasure

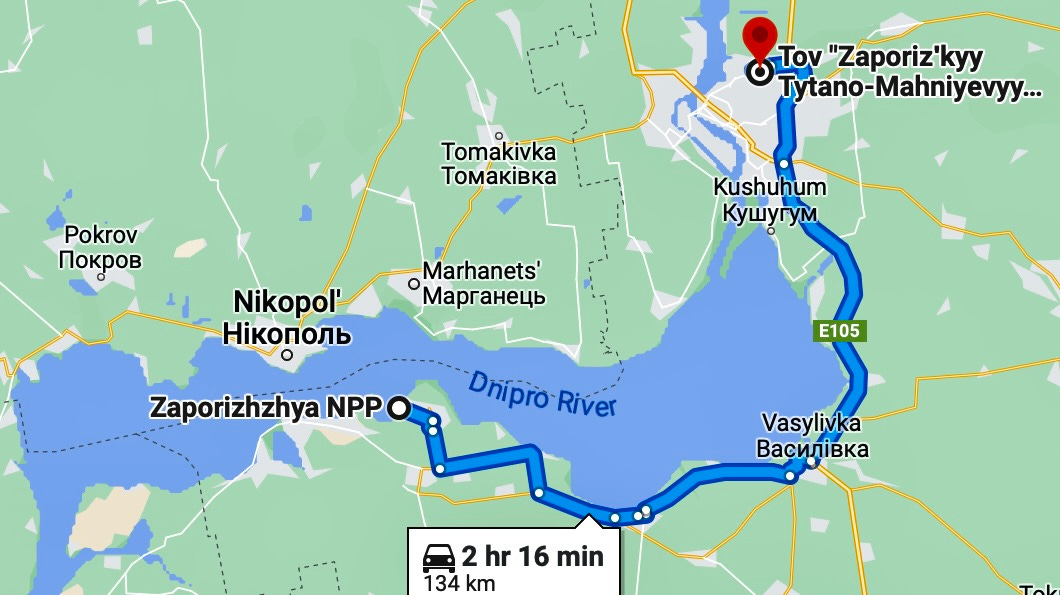

There has been much speculation lately, regarding the possibility of Ukraine launching an operation to recapture the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) or the possibility of ZNPP being struck by catastrophic false flag attack — time will tell. The ZNPP was captured by Russian forces in March 2022. Yet, there has been little discussion, that I have seen, on the fate of Europe’s sole Titanium sponge producer — Zaporizhzhia Titanium Magnesium Plant (ZTMP), which remains under Ukrainian control. Both ZTMP and ZNPP are located on the eastern bank of the Dnieper River. In terms of distance, ZTMC is situated approximately 130 kilometre's (81 miles), by road, north of ZNPP.

To get an idea of the strategic importance of ZTMP, lets take a brief look at what titanium sponge is and how its produced. Titanium sponge serves as the raw material for various titanium products used in aircraft, ships, tanks, missiles, prosthetic devices, and more.

The process begins with extracting titanium ore from mineral sand deposits, similar to gold panning. The ore is purified using electrostatic methods, followed by the energy-intensive "Kroll Process" for refining. This involves transforming the ore into titanium tetrachloride, separating it from chlorine, and reacting it with magnesium over four days, at a temperature of about 1,000°C. What’s left is pure titanium, but full of holes and is therefore called titanium sponge. Converting the sponge into ingots involves granulation, compaction, and vacuum melting. This energy intensive and lengthy process explains why titanium is about 15 times more expensive than aluminium. A step by step walk through video of titanium sponge production is here.

If aluminium is considered tokenised energy, titanium can be seen as the ultimate embodiment of this concept.

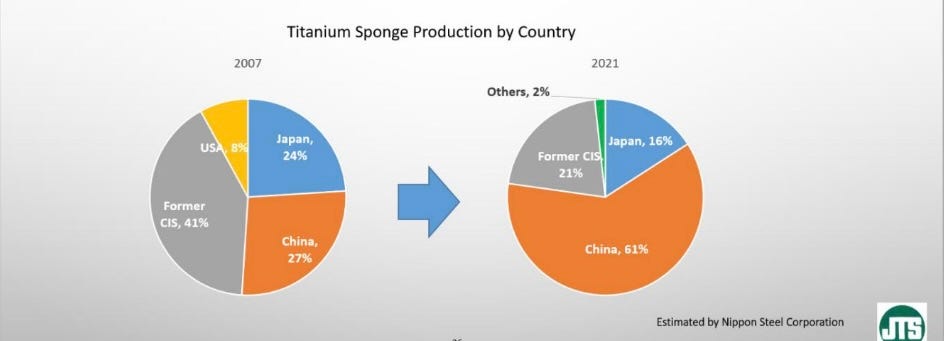

The production of titanium sponge is concentrated in a few countries, with China, Russia, Japan, and Ukraine being significant producers. These countries have abundant titanium reserves and advanced processing technologies.

The US Geological Survey reports that China is the world’s top producer of titanium sponge, accounting for 57 percent of global output at 210,000 metric tons in 2021. Japan was next at nearly 17 percent of global output, followed by Russia with nearly 13 percent of the market. Last year Kazakhstan produced 16,000 metric tons sponge and Ukraine produced 3,700 metric tons.

China and Russia have the capability to produce over 80% of the world's future titanium sponge production, easily within their grasp. And apart from Japan, other significant titanium sponge producers are either existing members of BRICS+ or are likely to become members in the near future.

Indeed, according to Nippon Steel Corporation of Japan, China's market share in the global titanium sponge industry was estimated at 61% in 2021, surpassing the 57% estimated by the US Geological Survey (USGS).

The U.S. no longer holds titanium sponge in its National Defence Stockpile, and the last U.S. producer of titanium sponge closed down in 2020. Despite this, titanium has been classified by the U.S. Interior Department as one of 35 commodities crucial to the country's economic and national security.

In relative close proximity to each other, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the adjacent Zaporizhzhia Thermal Power Station (which can be fuelled by coal, gas, or oil) along with the Nova Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station, generate substantial megawatt capacity that powers the region and beyond, including energy intensive industries such as ZTMP’s titanium sponge production. The huge overcapacity of Ukraine’s energy network and subsequent connection to Europe’s electrical grid, allowed Europe’s ENTSO-E, to import Ukrainian electricity.

On the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russian titanium producer VSMPO-Avisma sold its shares in Ukraine’s Demurinsk Mining.

On 30 September 2022, Russia announced that Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, despite only controlling part of the claimed territory, would become part of Russia. This almost certainly means, Russia will eventually take control over Ukraine’s ZTMP, together with all of the other infrastructure assets in these oblasts. Once control over Zaporizhia is consolidated, Russia’s market share of titanium sponge can only increase.

Titanium’s strategic importance is clear, China and the US are the two largest importers of titanium sponge (China also being the largest exporter of titanium), and Russia and Ukraine are both producers. Russia’s VSMPO-Avisma is the main supplier for France’s Safran, while Rolls-Royce gets about 20 percent of its titanium from Russia. Airbus relies on Russia for half its titanium. Boeing has recently “suspended” titanium imports from Russia and although I have not had sight of the latest data, I suspect Boeing’s move has created a tighter market for non-Russian titanium, potentially adding to Europe’s woes.

Europe does not produce primary titanium sponge, but it does manufacture titanium ingots by utilising imported titanium sponge or scrap titanium, and remains involved in the production of downstream wrought titanium products. However, in 2020, the overall production of titanium products in the EU plummeted by more than half to 12 kt from 20 kt in 2019. Among the EU Member States, France held the largest market share (65%) in the shipment of all titanium products in 2020, followed by Germany (14%) and Italy (11%).

Up until now, the EU has steered clear of imposing sanctions on Russian titanium, going as far as exempting it from trade restrictions. This I think, reveals the significance of maintaining uninterrupted titanium supplies to Europe.

…sanctions on Russian titanium would hardly harm Russia, because they only account for a small part of export revenues there. But they would massively damage the entire aerospace industry across Europe” — Guillaume Faury, Chief Executive, Airbus.

With titanium's vital role in defense systems like aircraft parts, missiles, armor plating, and naval vessels, Europe faces critical decisions. It can either set up its own titanium sponge production, import titanium sponge and expand finished product manufacturing, or directly import the finished titanium product. However, all these choices come with significant costs, especially as expensive imported LNG is currently being used while Europe is also dealing with the challenges of a financial system on life support, recession and civil unrest.

For Europe to spin-up titanium sponge production, would require a massive, sustained investment in infrastructure. And for titanium production to be competitive, it requires cheap energy, lots of it, and a nearby, easily transportable, source of titanium ore.

In response to soaring energy prices, European producers of aluminium and other non-ferrous metals cut their production during 2022, and there are indications that this trend could translate into a lasting decline in production levels. Europe’s deindustrialisation is a clear and present danger.

The wall-to-wall narrative within the collective West—that Ukraine could win—never stood up to objective analysis. Europe has been outthought, outsmarted, and outplayed, and is now facing defeat in the kinetic war, the financial war, and the diplomatic war with Russia. Sooner or later, the EU will have to confront reality and negotiate a new European security architecture, albeit on Moscow’s terms.

Even if US/NATO were able to enter into negotiations with Russia, from a position of strength, Russia will not give up the oblasts of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia; constitutionally it would also be a non-starter for them. Rather, it is looking increasingly likely that more of Ukraine, especially those areas with a majority ethnic Russian population, will eventually fall under Russian control.

A comprehensive security agreement with Russia, the likely medium-term outcome, could be negotiated now and provide the EU with much needed breathing space to take stock and begin addressing some of its systemic challenges. Any such agreement would likely arrest deindustrialisation and also ensure a dependable source of titanium from a neighbouring country. From now, until such an agreement is reached, Europe will continue to wither on the vine.

Good work